Understanding different perspectives about evolution

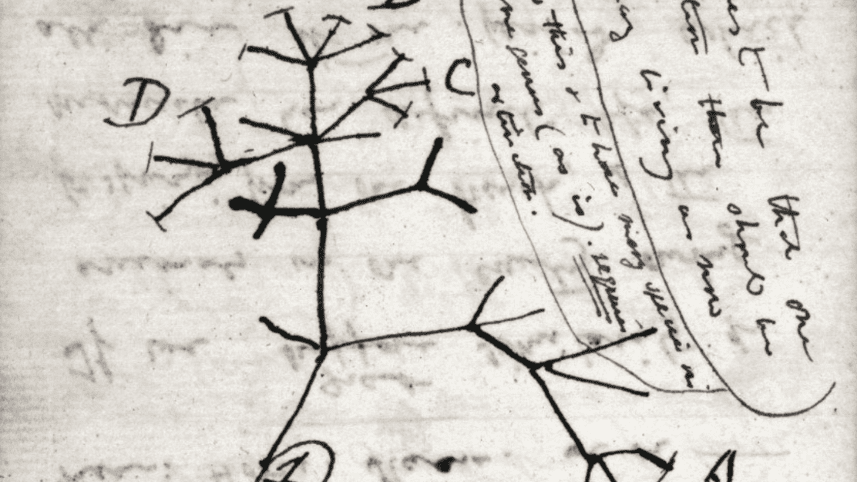

Throughout 2025 NCSE participated in many different events commemorating the centennial of the Scopes trial. At every event a similar sentiment was shared: can you believe we are still dealing with these same issues 100 years later? While I understand the frustration, as a science educator who has dedicated my career to studying how people make sense of evolution and climate change, I am not surprised that the issues surfaced in the Scopes trial are alive and well today. The fact is, evolutionary theory is complex and difficult to understand, and at the same time, it often seems to conflict with certain deeply held values and intuitive ideas people have about our place in the world. Of course, the intellectual tension between different ways of knowing is exactly why I love evolution so much! The science of evolution helps me make sense of the living world, and the philosophical implications of that understanding challenge me to integrate scientific knowledge with my cultural, religious, and political beliefs and values.

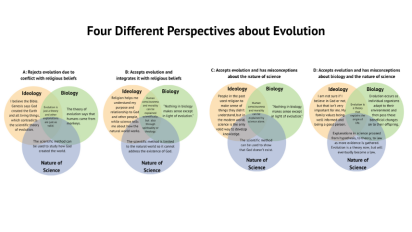

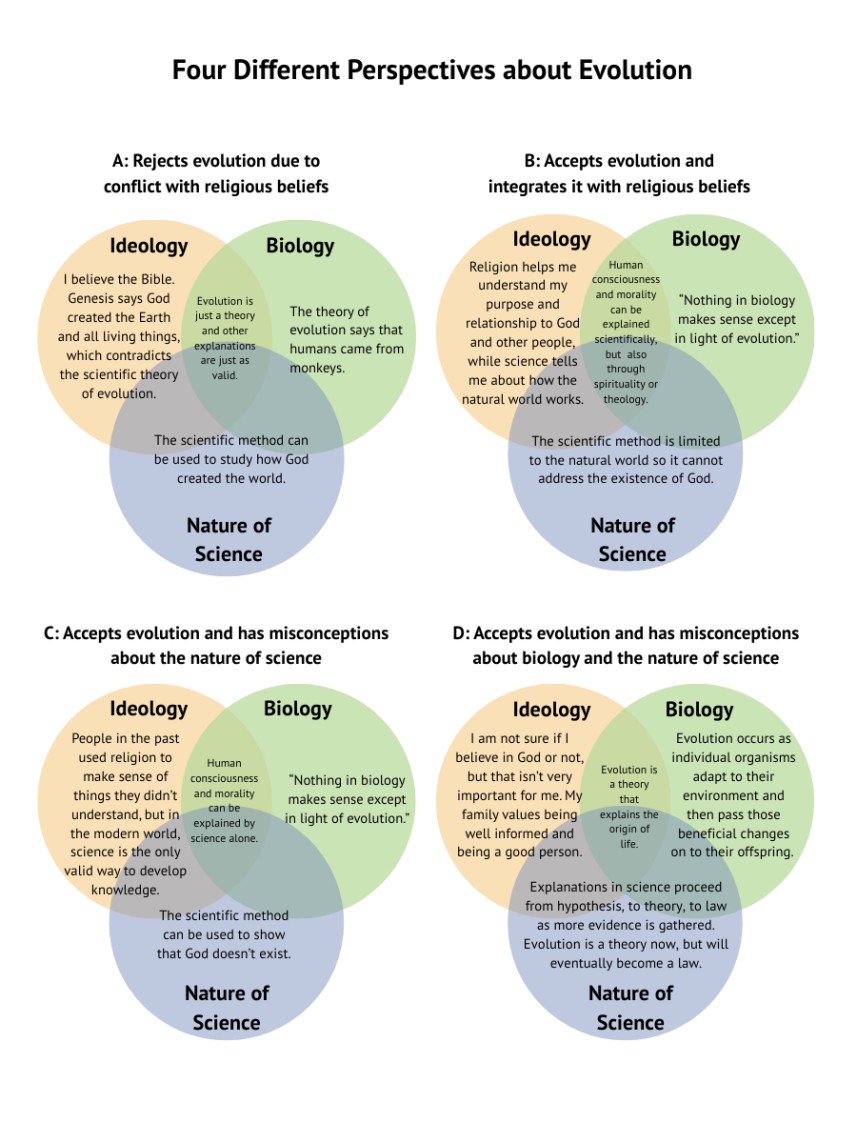

When discussing the challenge of teaching evolution with educators, I have found it helpful to use a Venn diagram to represent the relations among someone’s personal ideology, their understanding of biology, and their understanding of the nature of science. However, I also think this model is useful for anyone who attempts to discuss evolution with people who think differently than they do, because we know that empathy is the key to effective persuasion. If you hope to help someone reconsider their perceptions about evolution, you first need to understand how their perspective differs from your own.

Three overlapping domains influence our perceptions of evolution:

- Ideology: A person’s worldview, which is shaped by their personal experiences and their cultural, religious, philosophical, and political values and beliefs.

- Biology: A person’s understanding of biological processes and the mechanisms of evolution.

- Nature of science: A person’s understanding of how scientific knowledge is developed and used.

The infographic below uses the Venn diagram model to represent four different common perspectives about evolution (but there are many other perspectives not included here). You can think of these as representing simplified perspectives of four different individuals to illustrate how their ideology is related to their ideas about biology and the nature of science. Perspective A rejects evolution due to perceived conflict with religious beliefs, while the other three accept evolution. Religiously motivated rejection of evolution gets a lot of attention because this perspective is one of the driving forces behind anti-evolution legislation and vocal resistance in classrooms. Unfortunately, this sometimes leads to forming the belief that “religion is the problem” rather than recognizing that the challenges for evolution education are much more complex and nuanced. For example, perspective C accepts evolution, but holds the misconception that science can prove that God doesn’t exist. In contrast, perspective B accepts evolution while integrating it with religious beliefs. Religious belief in and of itself is not the problem, then. Rather, the main challenge for evolution education comes from those who do not understand that science is limited to naturalistic explanations of the physical world, especially if they attempt to use science to prove their ideological beliefs, whether those are religious or anti-religious.

Not only does each individual hold a complex and interconnected set of knowledge and beliefs, but also they respond to what they believe about other people’s perspectives. For example, when people publicly promote a perspective that uses science to discredit spiritual or religious ways of knowing (Perspective C), it only fuels anti-evolution efforts by people who reject evolution due to their religion (Perspective A). The common refrain of anti-evolution efforts from Scopes through today is that evolution is an evil conspiracy theory devised to turn people away from God (or more generally from morality or traditional values). Part of why we are still dealing with these issues 100 years after Scopes is because the most vocal proponents of Perspective A and Perspective C are in a heated battle that completely ignores all other perspectives (as well as the fact that many people who hold similar perspectives to their own choose not to force their perspectives on other people).

Perspective B represents a person who understands and accepts evolution and also integrates their ideology with an accurate understanding of biology and the nature of science. In this example their ideological beliefs are religious; but regardless of whether a person holds religious beliefs at all, they are certain to subscribe to ideological positions that are not scientifically testable (e.g. political views, cultural norms, philosophical beliefs, moral values, etc.). Effective science education should make the distinctions between science and other ways of knowing clear, while supporting students in personally integrating ideology, biology, and the nature of science. Personally integrating ideology, biology, and the nature of science can be intellectually satisfying and prepares people to effectively apply scientific information and reasoning in their everyday lives. We can help students develop this kind of integrated perspective by helping them understand how science differs from other ways of knowing and giving them plenty of opportunities to consider how they might integrate scientific information with other ways of knowing (e.g. discussion of biomedical ethics, conservation efforts, legal policies related to the environment or healthcare, etc.). Perspective D represents a person who accepts evolution, but holds multiple misconceptions about biology and the nature of science. This perspective can be challenging to detect and requires that educators are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to elicit and respond to students’ ideas. NCSE's Evolution Story Shorts are designed to help teachers uncover their students’ misconceptions and directly address them with evidence.

When presenting this “Different Perspectives” model to science teachers around the country, I’ve heard from them that they find it useful as they address challenges related to teaching evolution because it helps them to empathize with their students and to target their instruction to the specific ideas with which their students are struggling. The model also helps us as evolution education advocates more broadly to better understand the common misconceptions we encounter in public discourse around evolution as well as ongoing anti-evolution legal challenges. The fact that the issues raised in the Scopes trial continue to linger 100 years later is solid evidence that facts alone are not going to solve these problems. Just like so many other thorny political and social issues, addressing the challenges in evolution education requires a willingness to listen to perspectives that differ from our own in order to find common ground on which to build practical solutions.