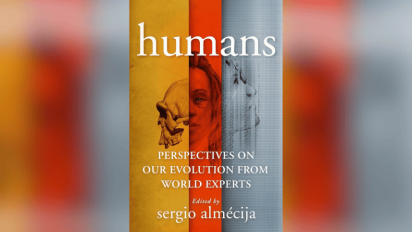

[Review] Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial that Riveted a Nation

"Those interested in the Scopes trial will enjoy this well-written account, as will readers wanting to know more about Bryan’s racism," our reviewer writes.

Brenda Wineapple’s Keeping the Faith is a good book about the Scopes trial, an often-discussed trial in 1925 in which high school teacher and coach John Scopes was prosecuted for violating Tennessee’s newly-passed law banning the teaching of human evolution in its public schools. Scopes’s trial became a sensational “media event” (before the term was coined) because it featured a face-off between two celebrities — Scopes’s defender Clarence Darrow and famed politician and religious leader William Jennings Bryan. Scopes’s conviction in Dayton was later overturned, but his trial left unanswered many questions that continue to spark debate, including who determines the school curriculum and how to resolve the tensions between science and faith in public schools.

Wineapple’s book is well-written and entertaining. Keeping the Faith sets up the Scopes trial well, covers most of the trial’s important events, and mentions all of the important participants. However, the reader has to wait for it. Indeed, the trial does not start until about halfway through the book. Moreover, although Wineapple’s extensive discussion of pre-trial events is accurate, it often focuses on portraying William Jennings Bryan as a racist. Certainly by today’s standards, Bryan was a racist, and racism was a popular part of the fundamentalist campaign. However, Bryan’s views about race — and racism in general — were not part of the trial. Wineapple’s discussion of the Ku Klux Klan might have been relevant to the passage of anti-evolution laws in other states (e.g., Oklahoma), but the KKK was not visible at Scopes’s trial.

Wineapple’s book is well-written and entertaining. Keeping the Faith sets up the Scopes trial well, covers most of the trial’s important events, and mentions all of the important participants. However, the reader has to wait for it. Indeed, the trial does not start until about halfway through the book. Moreover, although Wineapple’s extensive discussion of pre-trial events is accurate, it often focuses on portraying William Jennings Bryan as a racist. Certainly by today’s standards, Bryan was a racist, and racism was a popular part of the fundamentalist campaign. However, Bryan’s views about race — and racism in general — were not part of the trial. Wineapple’s discussion of the Ku Klux Klan might have been relevant to the passage of anti-evolution laws in other states (e.g., Oklahoma), but the KKK was not visible at Scopes’s trial.

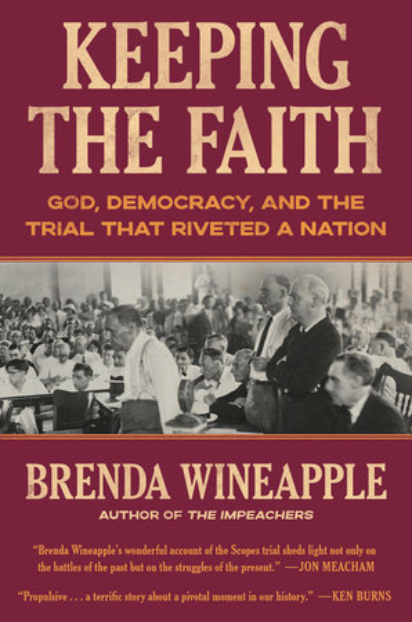

Attentive to Bryan’s racism, Wineapple overlooks similar faults of the scientists who supported Scopes and ridiculed Bryan. For example, she describes Scopes’s supporters as “liberal-minded men and women … who believed in the scientific method and progress,” but fails to note that many of the scientists who publicly condemned Bryan were fervent advocates of eugenics. These scientists twisted scientific findings to fit their social biases, promoting racial hierarchies and social inequalities as though they were simply biological facts. Many of these eugenicists were involved in the Scopes trial. For example:

- The American Association for the Advancement of Science’s “Committee on Evolution,” which met with Scopes and his attorneys before and during the trial, included Charles Benedict Davenport, whose Eugenics Record Office promoted eugenics as an applied form of heredity, and Edwin Grant Conklin, who wanted to forcibly sterilize people to preserve the purity and superiority of the white race.

- Famed paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, who hosted the Second and Third International Congresses of Eugenics, met with, advised, and gave money to Scopes before the trial. David Starr Jordan, Scopes’s leading fundraiser after the trial, believed that racial decay had resulted from “the survival of the unfit.” To Jordan, the racial superiority of whites was simply “the common observation of every intelligent citizen.”

- Several of the scientists who, unlike the members of the Committee on Evolution, came to Dayton to testify on Scopes’s behalf similarly strongly advocated eugenics and white supremacy. For example, zoologist Horatio Hackett Newman — the author of Evolution, Genetics, and Eugenics (1925) — promoted eugenics to “save [humanity] from racial degeneration.”

The textbook that Scopes used in his biology class (A Civic Biology, by George Hunter) included a much-discussed section promoting white supremacy titled “The Races of Man,” but there is no evidence that Scopes taught his biology students anything from this section of the book. However, Scopes quizzed his students about Hunter’s discussion of eugenics, and the quiz presumably reflected what he taught.

Wineapple’s discussion of the trial’s day-to-day events is accurate and flows quickly, but I was struck by what is missing from the narrative. In particular, Wineapple pays little attention to the testimonies of what she calls “students from Scopes’s class.” In fact, the two students who testified at Scopes’s trial were from different classes taught by Scopes. Harry Shelton testified that Scopes taught human evolution in biology, where the textbook included five pages about evolution. However, Howard Morgan — the only other student to testify — was in general science, where the textbook (General Science, by Lewis Elhuff) did not mention biological evolution. Nevertheless, Morgan testified that Scopes taught evolution — in a non-biology class that used a textbook that did not include evolution. This is why prosecutor Sue Hicks had announced on May 23, 1925, to the Knoxville News that “The state has an airtight case … In his class in general science, in which the textbook involved in the case [i.e., Hunter’s A Civic Biology] was not used, Scopes made statements to his students which are not in the text of the general science textbook. He went beyond the text and out of his way to teach the theory of evolution.” Other students (e.g., Jack Hudson) were ready to testify that Scopes had even taught evolution in his physics class.

After discussing the trial, Wineapple then excellently describes Scopes’s appeal of his conviction; this is a strength of the book. Keeping the Faith concludes with a short review of post-trial events (e.g., the production of Inherit the Wind) and a brief presentation of the post-trial lives of many of the trial’s participants. I wish this section had been longer.

Those interested in the Scopes trial will enjoy this well-written account, as will readers wanting to know more about Bryan’s racism. I would have liked to see more new facts or insights about the trial, but it’s a good read anyway.