The Ongoing Fight for Evolution Education

It’s been 100 years since the Scopes “monkey” trial captured national attention, placing evolution education at the center of one of America’s longest-running cultural debates. And yet, as we stand at this centennial moment, a question hangs in the air: Why are we still debating evolution in public schools?

The resistance to evolution isn’t just about facts. It’s about evolution outright. Many Americans don’t reject evolution because they misunderstand it — they reject it because it challenges core beliefs. Here at NCSE, we’ve learned that fighting misinformation with more information isn’t enough. We must meet communities where they are, listen deeply, and foster dialogue instead of debate. We must build trust before we can build understanding. That’s why NCSE doesn’t work with just policymakers and scientists — we work directly with teachers and communities. We help educators teach evolution with confidence and clarity, and we give them the tools to respond to resistance thoughtfully and respectfully.

In my role at NCSE, I see daily the renewed pressures and subtle challenges that science educators face, particularly around evolution. Today, our work is more urgent than ever. As we reflect on the Scopes trial in its centennial year — through commemorations like Vanderbilt University’s Scopes Centennial Symposium, of which NCSE was a co-organizer — we must remember that the trial wasn’t just about science. It was about the cultural fault lines of a nation grappling with change.

From the Butler Act’s ban on teaching evolution to John Scopes’s deliberate challenge, and with the ensuing media spectacle, Scopes v. Tennessee became a national moment. We often focus on the clash between Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan, or the courtroom drama that ensued. We forget that Scopes himself was not just a defendant — he was a willing participant in a symbolic showdown.

In July 2025, NCSE Deputy Director Glenn Branch and I, along with current and former board members including Kenneth R. Miller, Eric Rothschild, and Barbara Forrest, had the distinct pleasure of joining a host of other leaders in evolution education, evolutionary sciences, and history to share about the impact of the trial at the Scopes centennial event hosted by the Evolutionary Studies Initiative at Vanderbilt University. We spent two days learning from scholars in science, history, science and religion, law, museum science, and more about the impact of Scopes as well as perspectives moving forward.

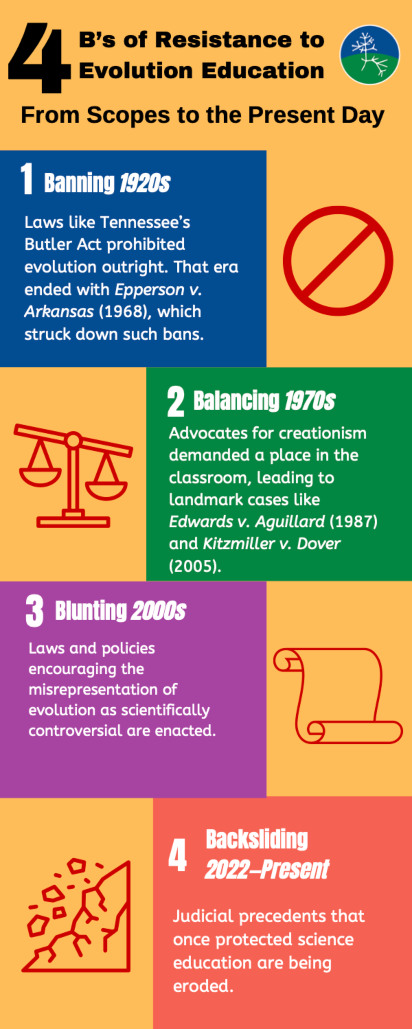

Since 1925, we’ve seen multiple waves of resistance to evolution in the classroom:

Banning (1920s): Laws like Tennessee’s Butler Act prohibited evolution outright. That era ended with Epperson v. Arkansas (1968), which struck down such bans.

Banning (1920s): Laws like Tennessee’s Butler Act prohibited evolution outright. That era ended with Epperson v. Arkansas (1968), which struck down such bans.

Balancing (1970s): Advocates for creationism demanded “a place in the classroom,” leading to landmark cases like Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) and Kitzmiller v. Dover (2005).

Blunting (2000s): Laws and policies encouraging the misrepresentation of evolution as scientifically controversial are enacted.

Today, however, we’re entering a new, dangerous phase: Backsliding. This fourth “b” represents a return to the bad old days. Judicial precedents that once protected science education are being eroded. The Lemon test, which helped courts identify violations of the Establishment Clause, has been sidelined. A recent case, Mahmoud v. Taylor, granted parents the right to opt out of classroom topics on religious grounds — a move that could open the door for evolution once again to be silenced.

Compared to the public battles of the past, today’s conflicts are quieter but no less dangerous. They happen at school board meetings, curriculum reviews, and closed-door conversations. At local and state levels, material on evolution is again being softened or removed from standards and books, and textbook chapters are being censored; challenges are happening in ways that make it more difficult for prior legal cases to be applied. Growing pressures from communities and districts on classrooms create a perfect storm for anti-science action to move into classrooms in ways that resemble fights of the past. Teachers are the heart of science education — but they’re too often underprepared and under-supported. Many lack specific training in evolution. Others fear backlash from parents or administrators. In states with teacher shortages, science classes may be led by educators from unrelated disciplines.

So where are we 100 years later?

Over the past century, significant progress has been made in the fight for evolution education. Today, evolution is included in the science standards of every state, and courts have consistently upheld the right to teach it. Technological advancements have also provided educators with powerful tools to access, share, and teach science more effectively than ever before.

Yet despite these gains, many of the core challenges remain unchanged. Cultural resistance to evolution remains deeply entrenched, especially in certain regions of the country. Religious fundamentalism continues to influence public attitudes and fuel skepticism toward evolution. And in many ways, classrooms still reflect the broader societal divides that first surfaced during the Scopes era — serving as battlegrounds for debates that extend far beyond science. The question we must ask now is: What do we want science classrooms to look like in 10 years?

Imagine a classroom where evolution is not a battleground but a gateway — a portal to understanding genetics, climate change, biodiversity, and the very story of life on Earth. As I often say, the Scopes trial was never really about one teacher in Dayton — it was about who gets to decide what our children learn. That question remains unresolved.

We need more than court rulings — we need public trust. The curriculum is only as strong as the support behind it. And that support is built through relationships, empathy, and sustained community engagement.